|

The Making of a Taylorologist

|

This is the history of my interest in the William Desmond Taylor case, and how my hobby grew and developed over the years. It’s hard to remember everything, but the following timeline should be pretty accurate. This is the history of my interest in the William Desmond Taylor case, and how my hobby grew and developed over the years. It’s hard to remember everything, but the following timeline should be pretty accurate.

In 1956, when I was nine years old, my family moved from Kansas to Southern California. Sometime in the early 1960’s, I obtained a copy of the booklet “History in Headlines: Major Events of the Past 75 years as Recorded on the Front Pages of the Los Angeles Times.’ I probably bought it at a swap meet or from a used book store. The historical front pages reproduced in the booklet were very interesting to me. Although I had studied American history in school, I knew almost nothing about the colorful history of Los Angeles.

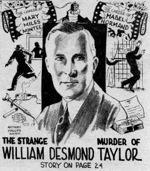

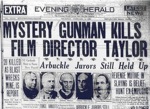

Among the front pages reproduced in the booklet, one that I found particularly fascinating was the page pertaining to the Taylor murder, with the explanatory caption: “The murder of a leading movie director, involving top members of the industry, was never solved.” How come I had never heard about this event? In public libraries, I tried to find out more about the case, with little result. No books had yet been written about the case, and the usual resources for finding magazine articles (like Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature) were of very little help, but I did examine the microfilm of the Los Angeles Times for the month following the murder. I was interested in learning more about the case, but did not know where else to turn for information. Among the front pages reproduced in the booklet, one that I found particularly fascinating was the page pertaining to the Taylor murder, with the explanatory caption: “The murder of a leading movie director, involving top members of the industry, was never solved.” How come I had never heard about this event? In public libraries, I tried to find out more about the case, with little result. No books had yet been written about the case, and the usual resources for finding magazine articles (like Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature) were of very little help, but I did examine the microfilm of the Los Angeles Times for the month following the murder. I was interested in learning more about the case, but did not know where else to turn for information.

In 1973 I read a newspaper article about Blackhawk Films, the company which reissued silent films in 8mm format. I had a Super 8 projector which wasn’t getting much use, so I bought a few of the silent films from Blackhawk. I liked them, bought more, and became increasingly interested in silent film.  I began reading about the silent film era, to get background information on the films and actors I was watching. In addition to the films themselves, I began collecting books and magazines pertaining to the silent film era, and I subscribed to Classic Film Collector, which was the cultural hub for people interested in silent films. I also began attending screenings at the Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles. I began reading about the silent film era, to get background information on the films and actors I was watching. In addition to the films themselves, I began collecting books and magazines pertaining to the silent film era, and I subscribed to Classic Film Collector, which was the cultural hub for people interested in silent films. I also began attending screenings at the Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles.

The Taylor murder case was mentioned repeatedly in books on silent film history, reviving my interest in the case (in particular, Mack Sennett’s autobiography, King of Comedy, which devoted three chapters to the murder). A few times I went to the L.A. Public Library and read everything I could find in the available 1922 contemporary newspapers published around the time of the murder. I also began using the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills, although their file on Taylor only had a few items. The Taylor murder case was mentioned repeatedly in books on silent film history, reviving my interest in the case (in particular, Mack Sennett’s autobiography, King of Comedy, which devoted three chapters to the murder). A few times I went to the L.A. Public Library and read everything I could find in the available 1922 contemporary newspapers published around the time of the murder. I also began using the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills, although their file on Taylor only had a few items.

Between 1973-1980 I was working for Kerr Steamship Company, in an office on the 23rd floor of the Equitable building, on Wilshire Blvd. in Los Angeles. I could look down out of the office window and see the former mansion of Mary Miles Minter and her family, at 7th and New Hampshire.

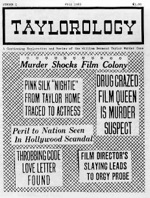

In 1977 I copied the 1922 Los Angeles newspaper interviews given by silent film stars in the weeks after the Taylor murder, edited those interviews into an article, and sent it to Classic Film Collector. They published it in the Winter 1977 issue with a nice graphic on the cover. In 1977 I copied the 1922 Los Angeles newspaper interviews given by silent film stars in the weeks after the Taylor murder, edited those interviews into an article, and sent it to Classic Film Collector. They published it in the Winter 1977 issue with a nice graphic on the cover.

But it seemed to me that aside from a few book chapters, magazine recaps, and the original newspaper articles, there wasn’t much else I could easily find out about the case. After I bought a VCR in 1979, silent movies became much less of my home entertainment because of the availability of sound movies and TV programs on video.

The publication of Betty Harper Fussell’s book Mabel in 1982 strongly re-ignited my interest in the Taylor murder case. Her book had some really good chunks of information about it, including the later flare-ups of the case in 1923, 1926, 1929 and 1937. I wrote to her, and a correspondence developed. This was really the first time I had someone to communicate with regarding the case, and I found it mentally very stimulating. In order to have something to write to her about, I felt I needed to come up with more information about the case, and about Mabel Normand. The publication of Betty Harper Fussell’s book Mabel in 1982 strongly re-ignited my interest in the Taylor murder case. Her book had some really good chunks of information about it, including the later flare-ups of the case in 1923, 1926, 1929 and 1937. I wrote to her, and a correspondence developed. This was really the first time I had someone to communicate with regarding the case, and I found it mentally very stimulating. In order to have something to write to her about, I felt I needed to come up with more information about the case, and about Mabel Normand.

I went to the Long Beach Public Library, to see what the coverage of the murder case had been in the Long Beach newspapers, and I was very impressed with the microfilm machines at the Long Beach Library, which could easily copy an entire newspaper page. (At the Los Angeles Public Library, photocopying from newspaper microfilm was at that time difficult, expensive, and only part of a page could fit into each copy.) I began a collection of photocopies of the newspaper coverage of the murder. I went to the Long Beach Public Library, to see what the coverage of the murder case had been in the Long Beach newspapers, and I was very impressed with the microfilm machines at the Long Beach Library, which could easily copy an entire newspaper page. (At the Los Angeles Public Library, photocopying from newspaper microfilm was at that time difficult, expensive, and only part of a page could fit into each copy.) I began a collection of photocopies of the newspaper coverage of the murder.

Meanwhile, in 1982 I had moved away from Southern California, to the Phoenix, Arizona area. Meanwhile, in 1982 I had moved away from Southern California, to the Phoenix, Arizona area.

At the Arizona State University library I discovered an unexpected treasure trove: Interlibrary Loan. Trying to examine microfilm at the Los Angeles Public Library had always been a hassle for me, due to expensive and difficult parking, traffic, limited time permitted on microfilm machines, etc. But at ASU these problems did not exist. Their on-hand microfilm library had less than a dozen publications of interest to me, but I learned that through Interlibrary Loan I could also order the microfilm from the LA Public Library, the California State Library, the Library of Congress, UCLA, and many other sources. At first I was only interested in what was reported in the Los Angeles newspapers, but my interest rapidly expanded and I wanted to see what every available national contemporary newspaper had to say about the Taylor case.

Some out-of-town newspapers had their own reporters on the Los Angeles scene in 1922. I soon found that the most sensationalized coverage of the Taylor case was printed in certain Chicago and New York newspapers. At that time the newspapers in major cities were publishing many editions every day, but the library microfilm for newspapers generally only had one edition on their microfilm (one rare exception is the New York Daily News — the microfilm for that 1922 paper has three editions for each day). So a story which originally appeared in a late edition Los Angeles newspaper might not appear in the library microfilm for that newspaper, but might be found in a wire service article printed in another city. Even with all the newspapers I have examined, I am sure there were many articles written about the murder in the five local L.A. newspapers which I have not seen. Out-of-town newspapers also often had editorials on the Taylor case, or editorial cartoons, or comments from visiting celebrities, or some ‘local angle’ to the case.

I soon realized that it was in my grasp to probably know more about the press coverage of the Taylor case than anyone else (which is not the same as knowing more about the facts of the case). The nonconformity of this research appealed to me very strongly. So I began ordering newspaper microfilm through Interlibrary Loan for the month of February 1922, guided by a library reference book indicating which newspapers were available on microfilm, and which libraries carried them. My collection of clippings grew and grew. At the time of the murder there were 14 daily New York newspapers, and I was able to examine them all (Times, World, Evening World, Herald, Tribune, Telegraph, Sun, News, American, Journal, Post, Telegram, Globe, and Mail). Eventually I was able to examine over 200 newspapers for the month of February 1922. I also began collecting the 1922 movie fan magazines which reflected the impact of the murder on Hollywood.

I applied for a job at Arizona State University, just so I could conveniently do my microfilm research there during my lunch hour and after work.

I wanted to do something with all the information I was accumulating, but what? I felt that I couldn’t really do a book on the Taylor case, since my material only covered the press coverage of the case, and did not reflect the actual investigation. I had been surprised to find so much humorous commentary regarding the case, so I assembled a volume containing the funny press items (“The Humor of a Hollywood Murder”), but was unable to find an interested publisher.

In 1985 I tried publishing a little fanzine on the Taylor case, called Taylorology which reprinted some of the choice material I had accumulated. I advertised in a dozen suitable publications, and printed 1000 copies, but only sold about 25. However, I sent free copies to a number of silent film historians. In 1985 I tried publishing a little fanzine on the Taylor case, called Taylorology which reprinted some of the choice material I had accumulated. I advertised in a dozen suitable publications, and printed 1000 copies, but only sold about 25. However, I sent free copies to a number of silent film historians.

My ads for Taylorology brought a response from Douglas Whitton, a Canadian who had been working on his own book on the Taylor case. We soon had a very lively correspondence, we freely shared our research with each other, and he invited me to collaborate on his book. It was clear to me that much more research needed to be done into Taylor’s years in Hollywood prior to the murder (1912-1922), so I began combing the Los Angeles newspapers and film trade publications for those years, looking for earlier items on Taylor.

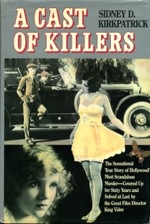

Whitton and I made a trip to Los Angeles in 1986, where we met each other and did some more research at the Herrick Library, UCLA, USC, the Long Beach Historical Society, and the Santa Barbara Public Library. We also met with Sidney Kirkpatrick whose book, A Cast of Killers, was on the verge of publication. Kirkpatrick showed us some fascinating material, including a letter written by Taylor, photos, and transcripts from the police file. He let us glance through his book and we had a long discussion with him about the Taylor case. We were also interviewed by a journalist who was writing an article about the case; that article was published in the Los Angeles Times on June 1, 1986. Whitton and I made a trip to Los Angeles in 1986, where we met each other and did some more research at the Herrick Library, UCLA, USC, the Long Beach Historical Society, and the Santa Barbara Public Library. We also met with Sidney Kirkpatrick whose book, A Cast of Killers, was on the verge of publication. Kirkpatrick showed us some fascinating material, including a letter written by Taylor, photos, and transcripts from the police file. He let us glance through his book and we had a long discussion with him about the Taylor case. We were also interviewed by a journalist who was writing an article about the case; that article was published in the Los Angeles Times on June 1, 1986.

Soon afterwards, Whitton and I decided to end our own collaboration. I thought it would be pointless to do our book without access to the official interrogation transcripts or similar sources detailing more of the actual investigation. Whitton wanted to proceed with his book anyway. To my knowledge, Whitton’s book is still unpublished.

Back in Phoenix, I wrote a second issue of Taylorology, listing what I perceived as errors in Kirkpatrick’s book. Only a few copies of that issue were printed; none were sold to the public — they were given to various silent film historians and libraries. This resulted in another media interview, for the January 1987 issue of Los Angeles Magazine. Back in Phoenix, I wrote a second issue of Taylorology, listing what I perceived as errors in Kirkpatrick’s book. Only a few copies of that issue were printed; none were sold to the public — they were given to various silent film historians and libraries. This resulted in another media interview, for the January 1987 issue of Los Angeles Magazine.

I corresponded with a number of writers on the silent film era, and freely gave them whatever assistance I could provide for their own book projects. In particular, I gave Robert Giroux a lot of material for his book on the Taylor case, A Deed of Death, and I later provided similar assistance for Charles Higham when he wrote Murder in Hollywood.

I wanted to do something with all the clippings I had accumulated on Taylor’s years in Hollywood prior to the murder, so I edited some of them into a very large third issue of Taylorology. Only four copies were printed; I kept one and sent the others to Anthony Slide, Kevin Brownlow and Robert Giroux.

Slide responded with an offer for me to do a book on Taylor as part of the Scarecrow Press Filmmakers Series. I was initially reluctant, but he persisted and I finally agreed. Fortunately I was able to obtain two accounts of the Taylor case written by investigators on the case (Ed. C. King and Leroy Sanderson). My book, William Desmond Taylor: A Dossier, was published in 1991. It resulted in a few local press interviews, including Phoenix New Times, and on-screen time for three cable TV documentaries on the Taylor case. Slide responded with an offer for me to do a book on Taylor as part of the Scarecrow Press Filmmakers Series. I was initially reluctant, but he persisted and I finally agreed. Fortunately I was able to obtain two accounts of the Taylor case written by investigators on the case (Ed. C. King and Leroy Sanderson). My book, William Desmond Taylor: A Dossier, was published in 1991. It resulted in a few local press interviews, including Phoenix New Times, and on-screen time for three cable TV documentaries on the Taylor case.

Between 1984 and 1991 a lot of my free time was devoted to library microfilm research into the Taylor case. In 1992 I married, and henceforth (except for my lunch hour) my free time was seldom occupied with further Taylor case microfilm research. Also, the increasing ease of Internet research makes traditional library research seem annoyingly tedious, even though most of the material is not yet available on the Internet.

In 1993 I resumed publishing Taylorology, in electronic form only, through the Internet. The electronic form appealed to me very much, because publication costs were reduced to almost nothing, regardless of the size of each issue, and distribution is effortless. After my book was published I still had an enormous amount of research material which had not been used in my book. I wanted to make more of that material available to the public. Future historians will undoubtedly want to re-examine Taylor’s life and death, and the impact of his murder on America. I want those future historians to have access to my material, to be able to use it as a foundation to build on. Placing a large chunk of material permanently ‘out there’ on the Internet increases the probability that future writers about the Taylor case will be able to utilize it, and help them avoid some of the many errors that are still being written about the case. Plus, I still had my old unpublished “Humor of a Hollywood Murder” manuscript. By serializing it within Taylorology, I could publish it that way. In 1993 I resumed publishing Taylorology, in electronic form only, through the Internet. The electronic form appealed to me very much, because publication costs were reduced to almost nothing, regardless of the size of each issue, and distribution is effortless. After my book was published I still had an enormous amount of research material which had not been used in my book. I wanted to make more of that material available to the public. Future historians will undoubtedly want to re-examine Taylor’s life and death, and the impact of his murder on America. I want those future historians to have access to my material, to be able to use it as a foundation to build on. Placing a large chunk of material permanently ‘out there’ on the Internet increases the probability that future writers about the Taylor case will be able to utilize it, and help them avoid some of the many errors that are still being written about the case. Plus, I still had my old unpublished “Humor of a Hollywood Murder” manuscript. By serializing it within Taylorology, I could publish it that way.

I also was hopeful that Taylorology would draw contributors of additional relevant information. There have been some very useful reader contributions (issues 35 and 84 in particular), but not as many as I had hoped.

By 2000 I was somewhat ‘burned out’ from producing an issue of Taylorology every month for seven years, so publication was suspended and I spent my spare time on other interests. But the 2007 availability of a portion of the police file on the Taylor case (courtesy of Sidney Kirkpatrick), plus my retirement from ASU and the recent Internet advent of new information venues like YouTube and Wikipedia, has begun to turn my attention back to the Taylor case again. In 2008 I began taylorology.com, to make even more information available to the public.

I regret that my shyness prevented me from ever attempting to contact anyone who had contemporary knowledge about the Taylor case; during the 1970’s and 1980’s several of them were still alive. But researching in solitude, pouring through old publications on microfilm or pounding my computer keyboard, is the realm I was comfortable in. I regret that my shyness prevented me from ever attempting to contact anyone who had contemporary knowledge about the Taylor case; during the 1970’s and 1980’s several of them were still alive. But researching in solitude, pouring through old publications on microfilm or pounding my computer keyboard, is the realm I was comfortable in.

|